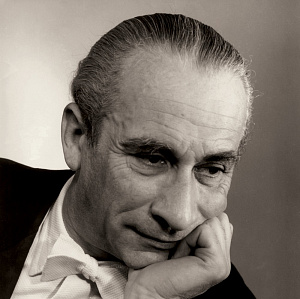

KAREL ANČERL - LIVE RECORDINGS

AN INTERVIEW FOR CRESCENDO MAGAZINE

Supraphon classical music chiefproducer Matouš Vlčinský made an interview for Crescendo magazine about the new compilation titled Karel Ančerl Live Recordings featuring previously unpublished recordings by one of the great conductors of the 20th century from the Czech Radio archives.

What does Karel Ančerl mean to you within the context of Czech music history and the “Czech conducting school”?

Karel Ančerl is today primarily known as a conductor who linked up to Václav Talich’s work with the Czech Philharmonic. By the way, he was actually a pupil of Talich’s. Ančerl was appointed music director of the Czech Philharmonic in 1950, and he would remain in that position for 18 (!) years. He managed to elevate them among the world’s finest orchestras and open for them the gates to the most prestigious concert venues. Moreover, he considerably expanded the Czech Philharmonic’s repertoire. Whereas Talich mainly focused on the music of Dvořák, Smetana, Suk and Janáček, occasionally performing pieces by Czech and other European Classicists, Ančerl naturally gravitated towards the 20th century, often presenting works by living, both Czech and international, composers. Ančerl thus included in the Czech Philharmonic’s repertoire music by Schönberg, Ravel, Bartók, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Honegger, Hindemith, Britten and other globally renowned creators. He performed pieces by older Czech composers, such as Suk and Novák, but also, frequently, by Bohuslav Martinů, Miloslav Kabeláč, Jaroslav Ježek and other contemporaries.

Noteworthy too are Ančerl’s achievements prior to the outbreak of World War II. In the 1930s, he gained recognition in Europe as a specialist in contemporary music. In Munich he assisted Hermann Scherchen in the exploration of Alois Hába’s quarter-tone opera Mother. Over the next few years, Ančerl was invited to contemporary music festivals in Vienna, Paris, Amsterdam, Strasbourg and Barcelona.

All in all, Karel Ančerl familiarised the Czech Philharmonic with global music, while he helped the world’s foremost orchestras to discover Czech music. Under Talich and Ančerl, the Czech Philharmonic definitely experienced the most rapid quality development in its history.

I assume that the album only features a fragment of the recordings that are maintained at the Czech Radio archives. How did you select the tapes for this compilation?

Our choice was based on three parameters: the repertoire, the performance quality and the technical condition of the recording. I did not want to include in the compilation works featured in the Ančerl Gold Edition (note: a series, consisting of 48 CDs of Karel Ančerl’s recordings, which Supraphon released between 2002 and 2008) in high technical quality. Yet the new collection may be even better regarding the repertoire the Czech Philharmonic under Ančerl performed at subscription concerts. Ančerl frequently presented works by his contemporaries, some of which, however, simply have not stood the test of time. Other recordings had to be put aside due to their poor technical quality. In some cases, the low quality is down to shoddy material or sloppiness during the actual recording process, while other tapes were damaged by multiple copying over the decades.

How do Karel Ančerl‘s studio recordings differ from his live recordings?

I would begin with that which they have in common: energy. Enthusiasm and involvement. When it comes to the differences, they are what can be expected: the studio recordings are refined in detail, whereas some of the recordings made at concerts reveal occasional lack of chime or imperfect intonation. We should, however, bear in mind that at the time live recordings were made at a single concert, with additional editing impossible. The current technologies could have corrected a few errors, but we decided not to change the recordings in this respect, thus preserving their documentary value to the full. These imperfections notwithstanding, I have to say that some of the recordings capture an immensely vivid atmosphere, the kind that is impossible to create in the studio. I believe listeners will agree that it more than makes up for the certain technical shortcomings.

A glance at the tracklist reveals there is a lot of contemporary music, contemporary in Ančerl’s time, that is. Does it reflect the repertoire featured in his concert programmes, or was it your choice with a view to highlighting the works that Ančerl did not record in the studio?

Ančerl was already deemed a contemporary music specialist in the 1930s. He even used to somewhat tease the “traditional” listeners, who ignored everything that was composed post World War I, finding anything newer offensive. Ančerl simply loved music, old and new, and he personally initiated performances of numerous pieces by his peers, both at home and abroad. In this respect, he was very progressive. Today’s young Czech composers may well sense the lack of an “Ančerl of their own”. Owing to him, many contemporary scores did not end up gathering dust in archives since we know them from recordings. Ančerl’s penchant for modern music was certainly enhanced by his having studied quarter-tone and twelfth-tone systems with Alois Hába, as well as – which is not generally known – percussion, due to which he acquired a great sense of rhythm.

The recordings in this box set were made between 1949 and 1968. Did Ančerl’s conducting style evolve between these two dates?

I am not sure about his style evolving, but I would say that over that time he deepened his understanding, particularly of the Romantic repertoire. What definitely did evolve was the rapport between him and the orchestra. At the beginning of his tenure, the Czech Philharmonic disliked Ančerl; following Rafael Kubelík’s emigration, the players had elected Karel Švejna as his successor, yet all of a sudden Ančerl appeared with a letter of appointment from the minister of culture. They deemed him an intruder, and it took years for them to set aside their distrust and begin perceiving Ančerl’s remarkable qualities. I think that the recordings show this process of gradual “thawing” and rapprochement. Oddly enough, Ančerl was not named music director of the Czech Philharmonic due to his being a member of the Communist party or thanks to the minister’s special favour, but owing to a recommendation on the part of David Oistrakh, based on his highly positive experience with Ančerl.

With the passage of time, some great artists fall into oblivion. Does the name Karel Ančerl still resonate among today’s young Czech artists?

I believe it does. I know a number of outstanding young artists who keep returning to Ančerl’s recordings, finding them truly inspiring. I personally consider the Ančerl era to have been the most significant Czech Philharmonic period, at least until the time of Jiří Bělohlávek’s second tenure in the post of principal conductor. As long as young artists seek inspiration in Ančerl’s artistry and see beyond his recordings’ technical limitations, he will remain part of the here and now.

What is Supraphon's policy as regards historical and archival recordings? Do you have any further plans in this respect?

I would like to remain on the general level. We intend to continue discovering historical recordings that have not yet been released, as well as reissuing previously released recordings that are extraordinary in terms of the quality of performance. Projects of such scope as this Ančerl box often depend on whether we receive sufficient finance, but I am convinced there is still a lot to uncover.

https://www.crescendo-magazine.be/karel-ancerl-en-perspective/